Translating from Japanese to English is more than converting words—it’s about bridging entire worldviews. Japanese relies heavily on context, tone, and hierarchy, while English favors clarity and directness. These cultural and linguistic differences pose immense challenges for translators. From the subtleties of humor to the intricacies of honorifics, localization professionals must strike a balance between authenticity and accessibility. In this article, we’ll unpack eight cultural nuances that often trip up even seasoned Japanese-to-English translators—and how experts navigate them with creativity and precision.

1. Honorifics: A Hierarchy in Words

Japanese honorifics like –san, –kun, and –sama reflect social hierarchy and relationships. English has no direct equivalent. Translators must decide whether to retain these suffixes or reinterpret them contextually. For instance, calling someone “Mr. Tanaka” instead of “Tanaka-san” may lose intimacy, while keeping –san preserves tone but risks confusing the reader.

2. The Subtlety of Politeness Levels

Japanese language is layered with politeness forms—plain, polite, and honorific speech (teineigo, sonkeigo, kenjougo). Translating these nuances into English requires contextual understanding. A single word like “taberu” (to eat) can vary dramatically based on who’s speaking and to whom.

3. Humor and Wordplay

Japanese humor relies on puns, double meanings, and timing. The manzai comedic style, for instance, doesn’t translate easily. English adaptors often use equivalent jokes instead of literal translations to preserve comedic rhythm, a practice evident in English dubs of anime like Gintama.

4. Unspoken Context (Aimai)

Japanese communication values ambiguity—the meaning often lies between the lines. Translators must read emotional cues, tone, and situation to fill gaps. For instance, “maybe” (*tabun*) could mean polite disagreement rather than uncertainty.

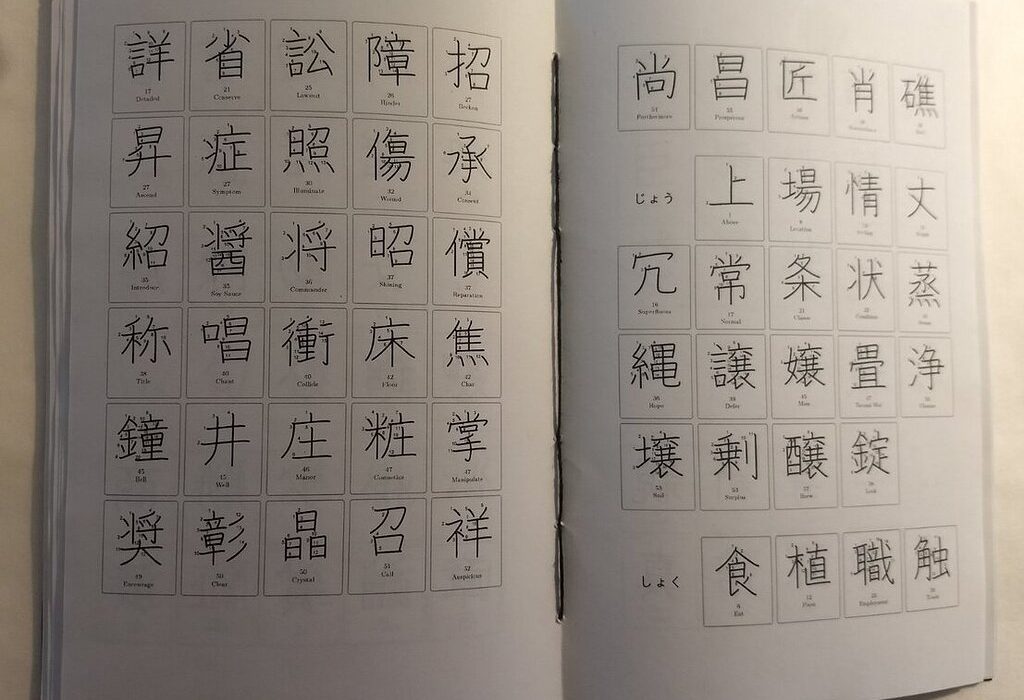

5. Onomatopoeia and Sound Symbolism

Japanese uses hundreds of mimetic words like dokidoki (heartbeat) and kirakira (sparkling). English lacks equivalents, so translators use descriptive phrases like “my heart raced” or “it shimmered brightly” to convey similar emotion.

6. Cultural Symbolism and Idioms

Expressions like “the frog in the well knows not the ocean” or “the nail that sticks out gets hammered down” carry profound cultural weight. Translators often find equivalent proverbs or rephrase them to retain the message’s moral essence.

7. Gendered Language

Japanese has gendered speech patterns—women traditionally use softer forms or sentence endings like *wa*. In English, gender is less linguistically marked, so translators adjust tone or word choice to reflect character identity subtly.

8. The Challenge of Directness

Japanese tends to avoid confrontation, favoring indirectness. English, however, values straightforward speech. Translators must gauge whether to preserve subtlety or make the dialogue more assertive to match Western expectations.

Conclusion

Mastering Japanese-to-English localization means balancing respect for cultural nuance with audience accessibility. Translators are not just linguists—they’re cultural interpreters. By understanding honorifics, humor, and unspoken context, they create bridges that allow global audiences to feel the story’s soul without losing its Japanese identity.

FAQs

1. Why can’t Japanese honorifics be translated literally?

They reflect cultural hierarchy, which English lacks, making literal translation ineffective.

2. How do translators handle Japanese humor?

They adapt jokes for timing and cultural relevance rather than direct translation.

3. What is “Aimai” in Japanese culture?

It refers to purposeful ambiguity—leaving things unsaid to maintain harmony.

4. Why are Japanese idioms difficult to translate?

Their meaning is deeply tied to culture, not just language structure.

5. What makes Japanese translation unique compared to other languages?

It intertwines emotion, context, and social etiquette—elements English handles differently.